Articles

AN AMERICAN GETS A HERO’S WELCOME IN ITALY

(The Wall Street Journal, May 2, 2000)

by Elin Schoen Brockman

The Italian publication of Harold Bloom’s new book, “How to Read and Why”, could not have come on a more auspicious date: March 8. All over Rome vendors were selling bouquets of brilliant yellow mimosas because it was International Woman’s Day. But in the early evening, as Mr. Bloom — renowned for his fierce battles against the teaching of politically correct but aesthetically challenged literature, and author of 24 books, including the best-selling “The Western Canon” and “Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human” — received an honorary degree from the University of Rome, it truly seemed as if Rome was in bloom because Bloom was in Rome. How clever of Rizzoli, his Italian publisher, to have capitalized on his presence here by publishing his book in this blaze of glorious mimosas.

Two days before, a jet-lagged Mr. Bloom was somewhat chagrined to find himself in a blank-walled office in the building which Rizzoli was in the process of vacating. He stared at an empty bookcase (a depressing sight for a man who owns upward of 30,000 books). Couldn’t he have been interviewed by journalists from every major newspaper in Italy as he sat in the Piazza Navona, gazing upon the Bernini fountain and its recumbent river gods?

“Maybe tomorrow,” said Rizzoli publicist Cristiana Zegretti, a little harried at having to squeeze nine interviewers into the next five hours (the press response to Mr. Bloom exceeded her wildest dreams). As if in compensation, a window was opened. And to the sounds of Vespas and heavy drilling, for nearly six hours, sustained only by acqua minerale and the oversized canapes known locally as tramezzini, Mr. Bloom held, for each journalist, what amounted to a private seminar on Western literature as only he can teach it.

Having placed his watch on the desk, as he has done before every class during 92 consecutive semesters of teaching at Yale, where he often becomes so passionately absorbed that he forgets his traditional break, he answered every question at length and in depth. His exhaustion (“as an old gentleman about to turn 70, I should no longer be taking overnight flights”) was quickly overcome by the reporters’ enthusiasm for his book, “which is meant to be a kind of companion for the solitary reader” — not to tell people what to read but rather how and why they should consider reading certain novels, poems, stories and plays that have been most important to someone for whom reading always has been almost the same thing as living.

“To the best of my abilities,” he told Monica Mondo of the Catholic daily Avvenire, “I tried to emphasize what I think the greatest use of reading is — which is to recover the self, to repair the self, to hearten and extend the self, and also, as the poet Shelley once put it, to learn to give up easier pleasures for more difficult pleasures.”

“In the end,” he said to Mirella Serri of Turin’s La Stampa, “reading…is the most profound of therapies. It renovates one.” And has he, personally found it therapeutic?” Ms. Serri asked in Italian like all her colleagues, and Mr. Bloom, who understands but is self-conscious about speaking Italian, answered, as he did throughout the interviews, in English. “Well, I went through the usual midlife crisis,” he said, “which indeed did happen in the middle of the journey at the Dantesque age of 35, and which two authors, Emerson and Freud, helped me survive, Emerson more than Freud. Emerson is the oracle. He teaches you what he calls the original virtue of self-trust. I don’t see how anything is going to benefit any of us more than Emerson…

“Except,” he added sotto voce to a friend who was sitting in on the interviews, “being in the Piazza Navona. By now I’d be on my second cognac, which would make my answers so much more interesting.”

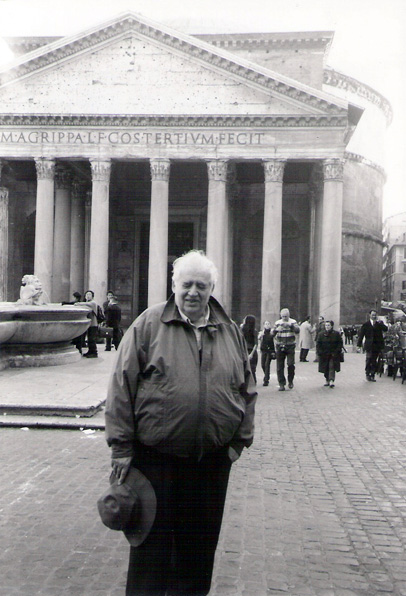

The next morning, from Trieste to Palermo, people are reading about “il grande critico americano” in their local newspapers. La Stampa calls him “an oracle of our time”. In Milan’s Il Giornale, he is described as “the Don Quixote of humanistic culture”, pursuing “the impossible dream”, battling the twin demons of political correctness and pop culture. (His response to this is: “Don Quixote? I’m more like Sancho Panza.”) By Thursday afternoon, having received his honorary degree and delivered lectures on Jane Austen and Hamlet to standing-room-only crowds, he is finally en route to the Piazza Navona, wearing his favorite Australian bush hat, arm-in-arm with his wife, Jeanne. By now his book is in the windows of most of Rome’s bookstores — but not, unfortunately, in the first one they see. “Ugh, John Grisham,” he comments, and they walk on. But in the next bookshop window, there it is: “Come Si Legge Un Libro (e Perche),” with its wonderful jacket — a trompe l’oeil photograph of books stacked in the shape of a Doric column.

The Piazza Navona is mobbed, flooded with sunlight, filled with the sounds of splashing water and troubadours and the squeals of exquisitely dressed toddlers terrorizing the pigeons. But what Paola Colaiacomo, professor of English literature at the University of Rome, calls “the famous Bloomian melancholy” is evident as Mr. Bloom settles himself at a table facing the Bernini fountain. It seems that the gastronomic slump that has occurred since he last visited Rome a mere three years ago — so many restaurants ruined by success; a McDonald’s staring the Pantheon in the face — is nothing compared to the reading crisis. This morning, introducing Mr. Bloom’s Hamlet lecture, his good friend Agostino Lombardo, Italy’s leading Shakespeare scholar, talked about Minister of Education Luigi Berlinguer’s systematic campaign to replace “elitist” studies such as classical literature in Italian universities — which are government-run — with “egalitarian” subjects like business English and computer science. This, Mr. Bloom says mournfully, is “even more pernicious” than the trouncing of humanism by multiculturalism in the literature departments of American universities, which are, for the most part, privately owned and therefore safe from government tampering.

“You know, some things in Rome are just as wonderful as they used to be,” he says, smiling sadly. “The splendor of the buildings, the quality of the wine, the quality of the light. But is this still going to be the city of the spirit if nobody is reading Dante or Shakespeare or Leopardi or Manzoni again? Or Calvino?”

The following week Mr. Bloom is buoyed, if exhausted, after lecturing to appreciative crowds on Othello in Venice, on Oscar Wilde in Bologna and Bergamo, and on himself in Turin. (“It’s not the speaking that wears me out; it’s the getting to the place where I’m speaking.”) And he’s even angrier at Mr. Berlinguer. “Everywhere I went, journalists, literary people, teachers, students said he’s going to single-handedly destroy university education in Italy!” In response to “anguished questions” from students at the Holden School in Turin (named for Holden Caulfield), “I told them that since Berlinguer describes himself as left-wing, he should really look at Leon Trotsky’s remarkable book called ‘Literature and Revolution’, in which he advises the budding writer to take Dante as a textbook because from Dante you learn how to read and write, according to Trotsky, and without Dante, you can’t learn how to read and write. I would add Shakespeare to that.”

Two weeks later, back home in New Haven, sporting the red suspenders that Mrs. Bloom bought him in Bologna, Mr. Bloom is “happily startled” upon receiving the news that his book has arrived in the No. 2 spot on the Italian non-fiction best-seller list. Could what he has written possibly help stem the decline of Italian literacy? “It won’t make a dent,” he says firmly. Then: “But one might modestly hope…”

from An American Gets a Hero’s Welcome in Rome

from An American Gets a Hero’s Welcome in Rome